Jiu-Jitsu: The Gentle Art?

Defining Terms

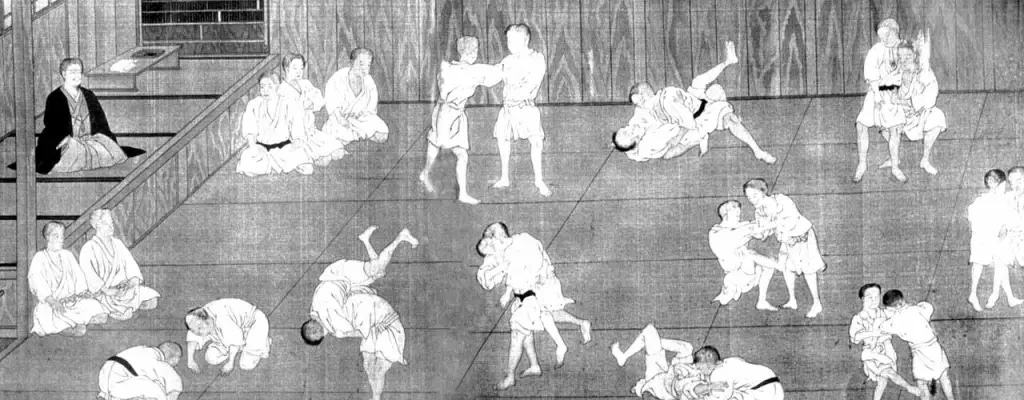

Jiu-Jitsu literally defined means “gentle art.” Historically, Jiu-Jitsu was comprised of many different schools of martial arts in Japan that all placed a similar emphasis on grappling. Although some of these schools – to a greater or lesser extent – utilized striking and weapons training, the general emphasis of the arts that were considered under the blanket term of Jiu-Jitsu favored grappling over striking. This may have been the original reason for the coinage of the phrase Jiu-Jitsu. Grappling is generally perceived as more “gentle” relative to the other competing martial arts in Okinawa, China, and India that emphasized striking.

Ideal and Myth

The popularity of the various martial arts represented under the general umbrella of Jiu-Jitsu – historically and in the contemporary world – is a function of the human desire for efficiency and utility. When presented with different means to achieve the same end, we will tend to choose the path that requires the least amount of effort. Martial arts that promote themselves as being effortless or near-effortless means to defeat opponents or defend oneself have obvious appeal.

This ideal of “minimum effort, maximum efficiency” veers into the fantastical realm of myth when it starts being promoted as “no effort, maximum efficiency.” You can see this in many of the ineffective martial arts – in terms of combat or self-defense – such as Aikido or Chin Na. A martial art that promotes itself as being a little-to-no-effort method for defeating larger or multiple opponents is engaging in deception. Combat and self-defense require a lot of effort, both in training and during direct application. All combat athletes know this, and long term students of Jiu-Jitsu know this as well.

Perception

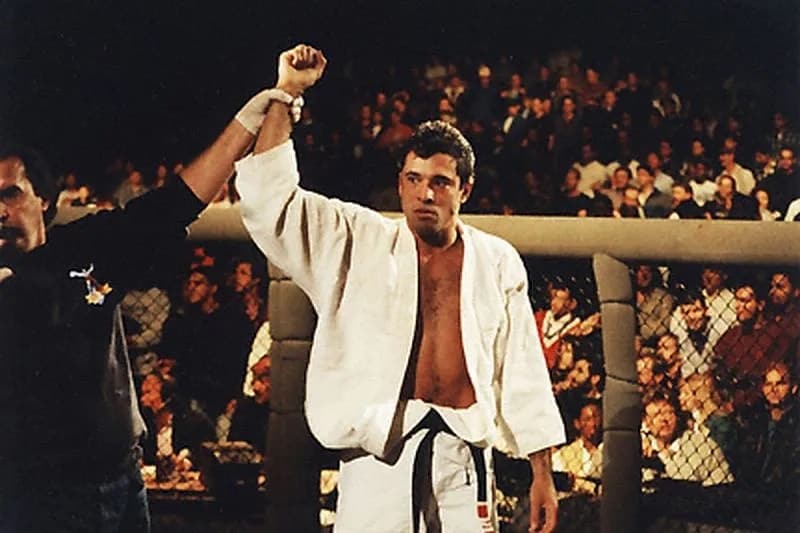

Many Jiu-Jitsu practitioners started training Jiu-Jitsu because of Royce Gracie’s performance in the first UFC, and the subsequent marketing of the Gracie family in the wake of that performance. A lot of us watched in awe as a skinnier man methodically defeated larger and stronger opponents while barely throwing any kicks or punches. It seemed like magic. It seemed like Royce was in possession of some secret techniques that allowed him to almost effortlessly defeat people he had no chance of otherwise defeating. Those of us enthralled by this performance felt that we had to learn the techniques of this “gentle art” that would allow us to effortlessly defeat people twice our size in combat.

Other students of Jiu-Jitsu were initially enticed by the idea that they could learn to control, dominate, and submit a resisting opponent while not dispensing any lasting damage upon them. Furthermore, the key to exercising this level of control wasn’t dependent upon size or strength or effort but on proper application of technique, leverage, balance, and body movement. Jiu-Jitsu really is “the gentle art.”

Reality

So you decide to start training “the gentle art.” You sign up for a Free Trial at a local Jiu-Jitsu academy. The reality of “the gentle art” soon presents itself in the form of a soul and diaphragm crushing knee-on-belly care package carefully wrapped and delivered by a 210 lbs. blue belt who smashed his way through your guard by underhooking both of your legs, stacking you onto your neck, grinding his cauliflowered ears into your hip, and dropping his chest onto your face. After crushing the breath out of your lungs like a nearly-empty tube of toothpaste, he proceeds to secure a kimura grip on your arm with his vice-like gorilla mitts, sits on your head, and carefully twists your arm behind your back until you tap. This is the “gentle art?” What exactly is “gentle” about this?

Ideal

Jiu-Jitsu doesn’t always feel very “gentle” when you’re on the receiving end, but that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t aspire to be as gentle as possible in order to achieve our goal, whether that be a dominant position or a submission.

The “gentle” in “the gentle art” refers to using the least amount of strength necessary, and instead relying upon proper position, body mechanics, leverage, balance, and gravity to achieve positional dominance and/or submission. Sometimes these “gentle” levers don’t feel very gentle on the receiving end, such as being on the bottom of a heavy pressure-pass.

However, when utilized properly, the techniques of Jiu-Jitsu require very little effort, strength, or raw aggression on the part of the attacker: and that’s precisely the point. That is why Jiu-Jitsu when living up to its ideal is an effective and devastating, yet ultimately “gentle,” art. Practitioners can subdue, dominate, and submit someone with very little aggressive force, strength, and overall energy. Again, this doesn’t mean that it feels gentle when you’re on the receiving end, only that the attacker is attempting to use as little strength and energy as possible to achieve his/her goal.

Temperance

“Minimal effort, maximum efficiency” is an ideal defined by relative terms, so is “the gentle art.” Sometimes the minimal effort needed to efficiently and effectively apply a technique or execute a movement requires quite a bit of effort. Similarly, sometimes we can’t be as gentle with a resisting opponent as we would a child or a kitten.

If we tried to hold the extreme of this ideal – that we should be literally gentle, or use truly minimal effort – we would either be smashed relentlessly or would be forced to transform Jiu-Jitsu into a hypothetical and fantastical art like Aikido or Chin Na, claiming to be able to force attackers into front flips with the merest flick of the wrist or disable their central nervous system with a precisely aimed knuckle strike. The reality that we face on the mat when we train every night dictates that we temper the ideal of the gentle art with the reality of combat: it is hard and it often requires a lot of effort and sometimes a not insignificant amount of strength.

So while we should always aspire to be as gentle as possible to achieve our goal, focusing primarily on technique, position, body mechanics, and leverage, don’t be surprised when you find yourself expending a bit more energy or using a bit more strength than the ideal dictates – whether on the “giving” or “receiving end.” Use this to think about how you could use less strength, less energy, and less effort the next time you find yourself in a similar situation. Sometimes you’ll be able to provide an answer, or your coach will, other times you’ll just have to live with the experience and settle for the unknown. After all, the journey is the goal.